Tukaram and Another v. State of Maharashtra (1978)

Ahaana Chowdhry

Indian Institute of Management, Rohtak

This Case Commentary is written by Ahaana Chowdhry, a Third-Year law student of Indian Institute of Management, Rohtak

CASE DETAILS

Court: Supreme Court of India

Equivalent Citation: 1979 AIR 185, 1979 SCR (1) 810

Bench: Justice Jaswant Singh, Justice P.S. Kailasam, Justice A.D. Koshal

Decided on: 15.09.1978

Parties:

· Appellant: Tukaram and another

· Respondent: State of Maharashtra

ABSTRACT

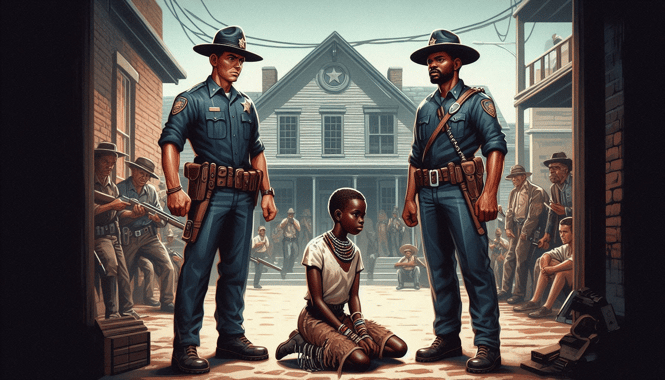

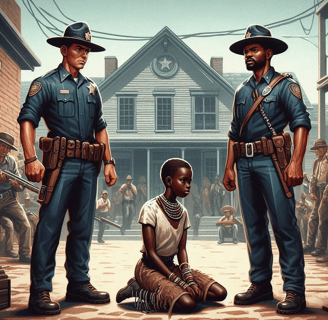

In the "Mathura Rape Case," a young girl of a tribal community called Mathura claimed that two policemen, Tukaram and Ganpat, had sexually assaulted her when she was being detained at the police station. The present matter was a major turning point in the legal discussion in India regarding rape regulations, as the ruling of the Supreme Court to release the accused sparked significant public indignation and riots. As a result, it sparked debates regarding the legal system's deficiencies in its handling of cases concerning victims of rape while in custody.

FACTS OF THE CASE

Mathura, an underage tribal girl, was conveyed to the Desai Ganj police facility in Maharashtra as a consequence of a minor household dispute. Mathura claims she was assaulted by two members of the police, Tukaram and Ganpat, while she had been in custody. Mathura's family members filed a complaint against the police officers after she informed them of their conduct.

The policemen had been cleared in the trial court because there was no evidence of struggle from Mathura and no visible traces of damage. Signs of acceptance were identified by the court in Mathura's submissive demeanour and the absence of physical harm. The Bombay High Court overturned the conviction on the appeal, determining that Mathura was unable to have willingly consented to the act due to the power inequalities and force in the prison environment. The court determined that the police officers had exploited their positions of power.

However, the Supreme Court reversed the ruling of the High Court and reinstated the verdict, arguing that Mathura's lack of resistance signified assent. The case was recognized nationwide as a result of the widespread outrage and unrest that it sparked, which underscored the shortcomings in the legal framework of India's management of rape accusations, especially within confined spaces.

ISSUES

1. Whether Mathura's assent was granted for the sexual intercourse with the officers?

2. Whether Mathura’s consent had been rendered invalid as a consequence of the coercive environment that existed within the police custody?

CONTENTIONS ON BEHALF OF THE APPELLANT

The appellants, Tukaram and Ganpat, argued that Mathura had consented to the sexual intercourse and that no unlawful force was employed during the event. The absence of any physical injury or evident signs of defiance was cited as evidence that Mathura had not been opposing the act in question, and that was interpreted as assent. The argument was cited as evidence that Mathura was not in opposition to the act. They contended that Mathura's conduct after the incident did not indicate any indications of trauma or objection, which bolstered their claim that the sexual interaction was entirely by choice.

CONTENTIONS ON BEHALF OF THE RESPONDENT

The State of Maharashtra, the defendant, contended that the victim, Mathura, offered credible and trustworthy declarations. They underlined that the victim's description of the incident was supported by the evidence presented and should be considered reliable. The defendant contended that whatever proof was available was ample for determining the crime of rape. They argued that medical results and the victim's assertions were sufficient to substantiate the punishment. The respondent maintained that the sexual interaction was not voluntary. They highlighted that the proof had demonstrated that Mathura did not permit for sexual conduct, which was an essential factor in the establishment of the offense of rape. The defendant upheld the prescribed methods that have been followed in this instance, contending that the decision rendered by the trial court was appropriately founded on the evidence and relevant requirements of law and that the correct process was adhered to. The respondent denied the accused's claims that the situation had been concocted or that there existed insufficient evidence. They emphasized that the prosecution's argument was based on reasonable legal standards and credible evidence.

JUDGEMENT

The Supreme Court ruled that the defendants were not guilty concluding that Mathura did not demonstrate opposition to the physical advances that were made to her and that her conduct indicated that she agreed to the sexual interactions. The court's decision was met with severe critique as a result of its inadequate comprehension of consent, which concentrated on the absence of physical pushback rather than the disparities in power and influence that are prevalent in detention-related situations. The court determined that the evidence presented was insufficient to establish that the sexual interaction was conducted without the approval of both parties involved in it, as Mathura failed to demonstrate any apparent signs of struggle or injury.

CONCLUSION

The ruling by the Supreme Court in the Mathura rape case sparked substantial protests and outcry among women's rights organizations. The verdict of the court, according to these groups, neglected the reality of oppressive circumstances surrounding incidents of rape happening in prison environments and encouraged blame-shifting. This resulted in significant changes in the law in India, such as the expansion of the definition of rape and the acknowledgment that the absence of physical violence is not proof of assent. This scenario led to the implementation of these revisions. The Indian Penal Code (IPC) was amended in 1983 as an aftermath of this case.

AFTERMATH OF THE CASE

In the wake of the Mathura Rape Case, prominent lawyers and campaigners began a wave of demonstrations. They felt the case brought to light major flaws in the judicial system and were unhappy with the way the Supreme Court handled it. It was felt that the two-finger test had an inappropriate impact on the evaluation of sexual assault cases because it was obtrusive and had certain technical issues. Among the most important things was this. Despite its widespread use at the time, this test lost some of its weight when it came to proving rape because the Court ignored it as insufficient evidence.

Some argued that the Court should have taken into account the power dynamics at play in institutional rape cases when it imposed its expectations on Mathura. Instead of concentrating on the misconduct of the police officers and Mathura's violated rights, the Court wrongly cast doubt on her consent and past sexual behaviour, suggesting that her involvement should be imputed.

As a result, in 1983, lawmakers in India added Section 228A to the Indian Penal Code as part of the Criminal Law Amendment Act, which aimed to protect victims' privacy while shifting the onus of proof onto those responsible. More severe penalties for custodial rape were also established by this Act, and in-camera sessions were mandated for rape trials. Further, in an open letter that emphasized the significance of civil rights and judicial impartiality, law academics called for a reassessment of the case.

REFERENCES

3. https://ijalr.in/tukaram-anr-v-state-of-maharashtra-case-analysis/