Repercussions of Cremation Ceremonies in River Ganga

Naman Sharma

Law Centre 2, Delhi University

This blog is written by Naman Sharma, a Second-year law student of Law Centre 2, Delhi University

Introduction:

Article 21 of the Indian Constitution declares and holds as fundamental a right to life and personal liberty, which essentially includes the right to a safe and healthy environment. Water pollution directly affects this constitutional guarantee because it undermines access to safe and potable water; such necessity is basic to sustain life. Health risks from contaminated sources/waterborne diseases were significant enough to contribute to the degradation of the environment and challenge the economy and the socioeconomic setup.

The Constitution of India recognizes access to clean drinking water as a constitutional right by drawing it from the right to food, the right to a clean environment, and the right to health which fall under the broad heading of Right to Life guaranteed under Article 21 of the Constitution. A detailed review of international treaties suggests that the drafters of the Constitution of India implicitly considered water to be a fundamental resource.

It was argued that Article 21 in itself covers the right to a healthy environment. The rationale of the judges was founded upon liberal thinking as a Principle, which was initiated from the rural litigation case and had enunciated an extensive interpretation of the word "life" in Article 21 itself by including environmental protection under the Right to Life.

The Supreme Court, in the landmark judgment also held that "the right to live 'includes the right of enjoyment of pollution-free water and air for full enjoyment of life.". If, perchance, any such thing endangers or impairs that quality of life in derogation of laws, it is well within the rights of a citizen to have recourse to Article 32 of the Constitution for removing the pollution of water or air which may be detrimental to the quality of life.[1]

Measures taken by the Government:

· According to the Central Pollution Control Board of India (CPCB), around INR 200 billion (USD 2.14 billion) was spent on cleaning the Ganga between 1986 and 2014. Since 2014, another INR 250 billion (USD 3 billion) has been allocated, of which more than INR 130 billion (USD 1.57 billion) had been spent by October 2022. The government has also changed its policies, taking a highly technical approach to cleaning the river.

The government claims that the project and its technology-first approach have succeeded where previous efforts have not. In January, the chief minister of Uttar Pradesh said the Ganga is so clean that foreign diplomats were bathing in it and dolphins were reappearing.

· The Indian government is touting Namami Gange as a "scientific program" that is all about high-tech wizardry in cleaning up one of the planet's filthiest rivers. Technically, this falls under the Ganga River Basin Management Plan (GRBMP), which was collectively prepared by seven schools of the Indian Institute of Technology, with IIT Kanpur heading the lot. The idea is that the water in the Ganga may at least be clean enough to take a bath in, even if not potable enough for drinking.

From 2015 to 2021, they constructed or planned more than 815 new STPs for just the Ganga. That's double the number of functioning STPs as of 2015. In Varanasi, there are seven STPs; four of those sprouted since 2014 because of the Namami Gange Programmed.

Measures Taken Under Namami Gange Project:

· Developing sanitary sewage treatment capacity- 63 sewerage management projects under implementation in the states of Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and West Bengal. 12 sewerage management projects were launched in these projects.

· Creating Riverfront Development- The state is starting 28 riverfront development projects along with 33 entry-level ones for building, managing, and sprucing up 182 ghats and 118 crematoria.

· Cleaning the river surface- It is all about gathering up the solid trash that floats on the ghats and in the rivers. Once we collect it, we pump that waste over to the treatment stations.

· Public Awareness: Seminars, workshops conferences, and various other activities are conducted to make people aware and increase community transmission.

· Industrial Effluent Monitoring: The Grossly Polluting Industries are monitored regularly. Industries following the set standard of environmental compliance are checked. The reports are sent directly to the central pollution control board without any involvement of intermediaries.[2]

Ganga Action Plan and National River Ganga Basin authority role:

On average approximately The Ganga Action Plan (GAP) was launched by the former Prime Minister of India, on June 1986 covering 25 Class I towns (6 in Uttar Pradesh, 4 in Bihar, and 15 in West Bengal);

Rs. 862.59 crore were spent in total. Its main objective was to improve the water quality by the interception, diversion, and treatment of domestic sewage and to prevent toxic and industrial chemical wastes from identified polluting units from entering the river.

NRGBA (National River Ganga Basin Authority) was established by the Central Government, on 20 February 2009 under Section 3 of the Environment Protection Act, 1986. In 2011, the World Bank approved $1 billion in funding for the National Ganga River Basin Authority.

Even after the implementation of NRGBA and GAP, no special measures were taken by proper government authorities to control the pollution caused by the disposing of dead bodies for funeral rites. We have collected the recent data of the river Gomti of India surveyed by Lucknow Nagar Nigam for studying the effects of cremation on the holy rivers of India.

Data showing pollution occurred because of cremation ceremonies in River Ganga:

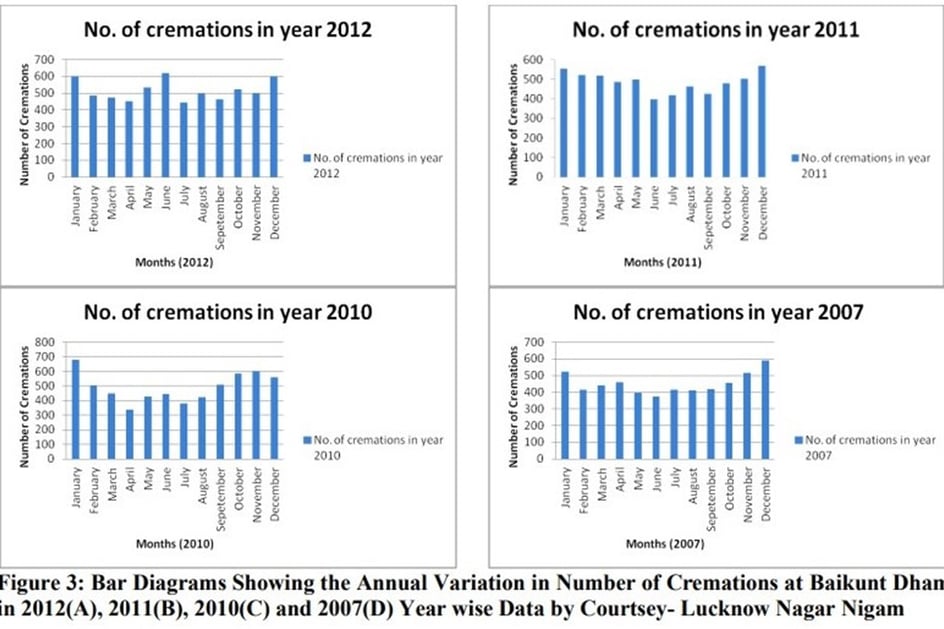

For the present study, data was collected from Baikunth Dham Cremation Center. This study provides the data of ash of dead bodies poured into the river, the quantity of wood and fuel used for burning dead bodies, number of deaths per year within the Lucknow urban center. All these data provide basic information to understand and to present an overview of the present-day impact of pollution on the Gomti River at Lucknow which is a tributary of River Ganga from this data, we can understand that the pollution incurred because of cremation ceremonies is increasing year by year.[1]

The number of cremations is increasing year by year and due to this pollution is also rapidly increasing in River Ganga.

The aftermath of using the river as a cremation center:

· It has been estimated that in four centers organizing the cremation of dead bodies, about 5300 people are cremated every year on average in only one of them is Baikunt Dham. By and large, about 300 kg of wood is needed for the cremation of a single dead body which varies from person to person and is responsible for environmental pollution. The figures take an Exaggerated form when the amount of wood is multiplied by the average number of deaths per annum.

· 20 to 25 kg of ash is produced by the burning of a single dead body. The Estimation of several cremations in a year is shown in the annexure attached. This clearly shows the massive increase in cremations with time even after the implementation of various programs like the GAP and NRGBA.

· The river is abused by those who worship it; Hindu rituals, such as placing dead bodies and cremation ashes into the water, quickly defile its sanitation. Many families cannot afford a proper burial or a complete cremation due to the high price of fuel wood. Others wish to bestow additional luck in the afterlife to the deceased and often use the river as a cemetery.

Is this Practice Necessary?

· The disposal of unburnt bodies into the River Ganga is not an important religious practice in Hinduism. Hindu tradition predominantly advocates cremation as the preferred funeral rite, with the ashes then reverently scattered into sacred rivers like the Ganges. This act symbolizes the cycle of life and death and is believed to facilitate the soul's journey to the afterlife. However, disposing of unburnt bodies into the river does not align with established Hindu religious teachings or customs.

· Rule 3 (17) of the Hazardous and Other Wastes (Management and Transboundary Movement) Rules, 2016 defines “hazardous” as any waste which because of characteristics such as physical, chemical, biological, reactive, toxic, flammable, explosive, or corrosive, causes danger or is likely to cause danger to health or environment, whether alone or in contact with other wastes or substances. Applying the said definition, the wastes or substances generated from fire industries would qualify as “hazardous waste”.[1]

· The Court, in the exercise of its parens patriae jurisdiction, to preserve and conserve rivers Ganga and Yamuna, declared the rivers, and all their tributaries, streams, and every natural water flowing with continuous or intermittent flow, as juristic/legal persons/living entities, having the status of a legal person with all corresponding rights, duties and liabilities of a living person read with Articles 48-A and 51-A (g) of the Constitution. I.e. the human face is bound to protect, conserve, preserve, uphold the status, and promote the health and well-being of Ganga and Yamuna. The Court made it clear that “Rivers Ganga and Yamuna are breathing, living, and sustaining the communities from mountains to sea.[2]

· In a landmark judgment, it was observed that in consequence, the polluting industries are "absolutely liable to compensate for the harm caused by them to villagers in the affected area, to the soil and the underground water, and hence, they are bound to take all necessary measures to remove sludge and other pollutants lying in the affected areas.". The "Polluter Pays" principle this Court has interpreted to mean that the absolute liability for the harm given by pollution extends not only to compensate the victims of pollution but also costs of restorative measures to be taken to repair the environmental degradation. The cost to reverse the damaged ecology would also be borne by the polluter as part of the process of "Sustainable Development" and, therefore, is liable to pay the cost to the individual sufferers as well.[3]

· The precautionary principle as well as the polluter pays principle have entered into the books of law. Article 21 of the Constitution of India further extends protection to life and personal liberty. Moreover, the principle demands that the state is required to take environmental measures 'to anticipate, prevent and attack' the causes of environmental degradation. [Prevention].

· Where, for example, there is a serious or irreversible risk to human health or the environment, scientific uncertainty should not serve as a basis for deferral of action to prevent environmental harm. [Precautionary principle].

· The Precautionary Principle is the very characteristic of the principle of 'Sustainable Development' - In case of doubt, the protection of the environment would have precedence over the economic interest Precautionary principle requires anticipatory action to be taken to prevent harm and that harm can be prevented even on a reasonable suspicion.[4]

Conclusion:

While the Ganges holds immense spiritual significance for Hindus and is revered as a goddess, the act of disposing of unburnt bodies contradicts principles of cleanliness, purity, and respect for life. Such actions can also pose environmental and public health risks, leading to pollution of the river and potential transmission of diseases.

Despite the implementation of initiatives like the Ganga Action Plan (GAP) and the National Gargi River Basin Authority (NRGBA), the problem of environmental pollution in rivers like the Gomati persists, particularly exacerbated by the disposal of dead bodies during funeral rites. The alarming data reveals a stark reality of increased cremations and the consequential release of harmful compounds into the river, contributing to its pollution. While legal frameworks exist, including the "Polluter Pays" principle and Article 21 of the Constitution of India, effective enforcement and proactive measures are imperative to address this pressing environmental issue and safeguard the sanctity of rivers like the Gomati for future generations.

Though there may be cultural or regional variations in funeral practices within Hinduism, disposing of unburnt bodies into the Ganges is not universally recognized or endorsed as a religious practice. Efforts by environmental and civic authorities aim to discourage such practices to safeguard both the sanctity of the river and public health.

In the name of disposing of the Ashes of the dead, people are also throwing half-burnt dead matter and even poverty-ridden people are not able to manage Firewood for the final rights of their people. So they dispose of the dead bodies without properly burning them which pollutes the river and is one of the main reasons for Communicable diseases.

In short, dumping half-burnt bodies into the Ganges doesn't match Hindu beliefs, which usually involve cremation and scattering ashes in rivers. This practice goes against cleanliness, purity, and respect for life, plus it's bad for the environment and public health. Authorities are trying to stop it to keep rivers sacred and people safe. Laws recognizing rivers as legal entities and calling funeral waste hazardous highlight the need to protect these important waterways.

References

[1] Subhash Kumar vs State of Bihar, AIR 1991 SCC (1)

[2] Abhinav Anand, ‘Ganga Pollution Case: A case study (2020) Ipleaders https://blog.ipleaders.in/ganga-pollution-case-a-case-study/ accessed 14th September,2024

[3] Uma Shankar Maurya and Anshu Mati Sharma ‘IMPACT OF CREMATION CENTERS IN RIVER POLLUTION: A CASE

STUDY FROM GOMTI RIVER, LUCKNOW, UTTAR PRADESH, INDIA(2016) International Journal of Geology, Earth & Environmental Sciences (ISSN) https://www.cibtech.org/J-GEOLOGY-EARTH-ENVIRONMENT/PUBLICATIONS/2016/VOL_6_NO_3/02-JGEE-002-MAURYA%96IMPACT-INDIA.pdf last accessed 15th September,2024

[4] Sankareswari vs The District collector, 2023 SCC Online Mad 407

[5] Mohd. Salim v. State of Uttarakhand,2017 SCC Online Utt 367

[6] Vellore Citizens Welfare Forum vs U.O.I.& Ors, 1996 (5) SCC 647

[7] T.N. Godavarman Thirumalpad vs U.O.I.,2022,10 SCC,584